Even though the global merger & acquisition (M&A) market declined in 2023, the total deal market value was still 3.2 trillion dollars, and is expected to grow yet again in 2024. Despite the popularity, between 60-90 % of global M&As fail. Managing organisational identity and brand-architecture strategy often gets neglected in M&A processes while this, in fact, plays a crucial role in the long-term profitability of the new entity.

Why do M&A deals fail?

As confirmed by several studies, between 60-90 % of all mergers and acquisitions fail and end up destroying rather than creating or maintaining shareholder value. The results range from devaluations, an exodus of talent, rapid subsequent divestiture of the acquired company or even bankruptcy. While aligned on the odds, the reasoning behind high failure rates differ. In an M&A survey from Boston Consulting Group among corporate leaders, four of the most cited reasons for deal failure relate to post-merger integration. While up to 90 % of all companies have standardised processes for deal preparation and deal execution, only 40 % of those have similar procedures for the integration phase in place. If the integration process gets management attention, financial and operational due diligence and the integration of logistics, production and personnel are often the dominating points of interest. What is often overlooked by both managers and most studies is how changing organisational identities impact the post-acquisition or merger success and the long-term performance of the new entity.

If managers do turn their attention to questions of identity, branding or brand architecture strategies, this often happens too late, to solve already occurred challenges instead of preventing them. Damage to customer satisfaction, valuation of the company, or employee morale has already happened and is difficult to turn around. Instead, IDna Group recommends working with an identity-based strategic approach while heading into a merger or acquisition in order to select the most fruitful acquirees, predict M&A success, and decide on the most profitable integration method.

Organisational identity

Organisational identity is defined as the “Who are we as a company” and probes organisational goals and values. To be considered part of organisational identity, attributes must be either central, enduring, or distinguishing. At IDna Group, we believe that identity is the only truly sustainable competitive advantage. Everything else can be copied or bought. During the last decade, we have helped many Nasdaq Copenhagen top 25 listed companies in Denmark and Europe to harvest the power of their identity, often in connection with mergers or acquisitions. In the process following the signed deal, two companies with their individual identities shall come together – setting off a new strategic direction and deciding whether or not to combine identities is not a trivial exercise.

Identity in the pre-merger and pre-acquisition phase

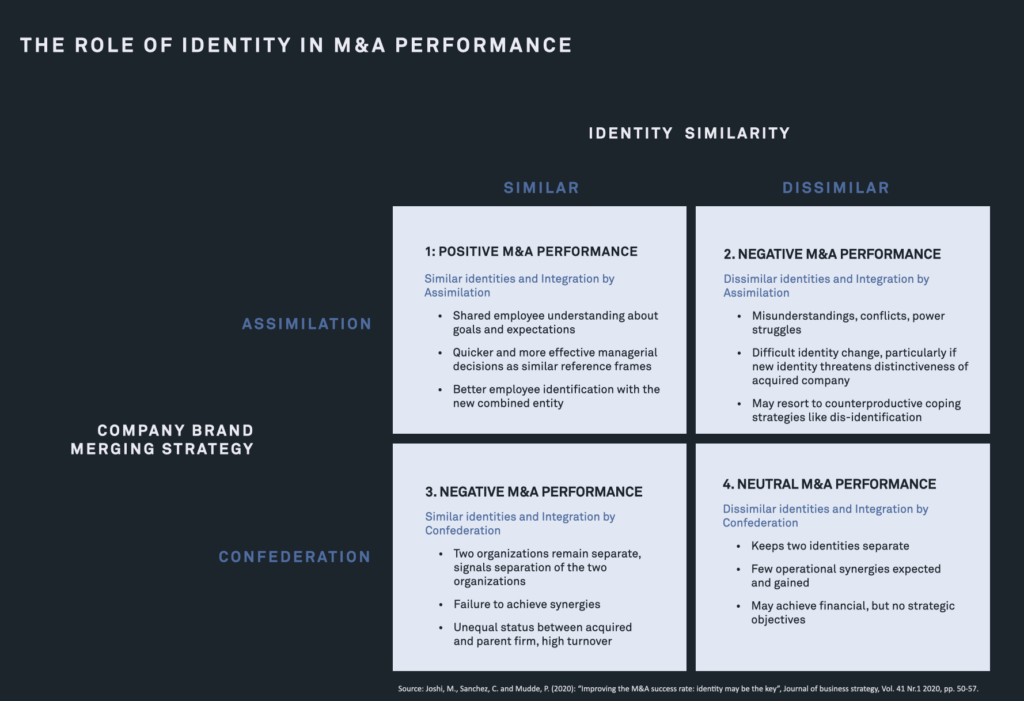

The similarity or dissimilarity in the identities of two firms – the acquiring and the acquired – is a key factor that will influence the profitability and performance of the combined entity. If the two separate entities share a similar understanding of who they are as a company, their goals, and what makes them unique in their modus of operating, the integration process with assimilation has a high chance of succeeding. Clients, partners and employees will connect to the new or combined entity more easily as they will be able to relate to its identity. However, in reality, it is often the case that companies wish to merge with or acquire a company with a dissimilar organisational identity in place. This creates an uneven, more complex, and challenging integration task, if not an impossible one.

How can managers in M&A processes use identity insights for increasing their M&A success?

1 – Select fitting companies

If the acquiring company has several options to choose from, the similarity or dissimilarity between organisational identities should be considered as a weighting factor as it predicts the success of integration and therefore long-time profitability.

2 – The value of an identity integration process in hostile takeovers

In hostile takeovers, the company to be acquired often reacts with defence and resistance. Our experiences show that numbers and rational arguments will not help negotiation in these situations. Being able to show a shared vision and an integration process that understands, respects, and acknowledges the organisational identity of the aimed entity does help to ease the way for closing the deal and therefore the success of the enterprise.

3 – Prepare both organisations for the integration phase and manage expectations

Suppose a merger or acquisition will proceed although the screening of organisational identities raised a red flag. In that case, it is crucial for management and decision-makers to be aware of the risks and challenges ahead and how to tackle them in order to beat the odds. Understanding integration possibilities and their associated pros and cons help navigate and build more realistic expectations towards the future entity.

Without calculating the success limiting factor of dissimilar identities, managers and shareholders often tend to develop unrealistic expectations and pay overvalued prices – a key indicator for disappointment at the post-merger state when reality sinks in. On the other hand, a clear integration strategy can make the transition much smoother and provide useful opportunities to deliver a strong message internally and externally regarding the value of the combined entity (source).

Identity in the post-M&A integration process

After closing the deal, the integrational phase starts – a phase that will determine the new entity’s future success and profitability for many years to come. Most integration processes aim to gain the highest synergies possible. However, if M&A architects forget to start planning the integration process according to the similarity or dissimilarity of organizational identities, all efforts to create synergies may fail before they even started.

Before integration can start, there is an important decision to make: The method of integration. Or to put it in other words, the question of whether to assimilate the acquired entity into the acquirer or reverse, to create an entirely new company, or to give permission for the acquired company to remain as an independently run part of the organisation (confederation). Companies with similar identities reach their best post-M&A results through assimilation, as the full synergies can get utilised. For companies with dissimilar identities, however, Joshi et al. suggest choosing the method of confederation instead (keeping entities separate), as the attempt to assimilate historically fails and results in negative M&A performance.

Although identity provides a very insightful perspective on this decision, it is not the only perspective to consider. Brand architecture strategies should equally play a role and must be considered. If a company has defined its optimal brand architecture strategy, we urge to maintain that strategy for the future health of the entire organization.

1 – Acquirers with a House of brands strategy

In a house of brands strategy, the integration question often seems obvious, the acquired company becomes just another separately run brand. However, growing through M&A with a house of brand strategy in place often leads to a crowded portfolio of brands that are not necessarily structured according to market needs and competitiveness. As a house of brands is the least efficient brand strategy in place, managing an overly crowded portfolio of brands can present strong financial challenges that weaken the overall performance unnecessarily. We, therefore, suggest evaluating the strengths of the portfolio and the question of merging brands with similar value propositions and identities on a regular basis.

2 – Acquirers with a One brand strategy

Organisations that have been historically successful due to a One brand strategy, should not give an acquired company permission to stay independent, although dissimilar identities may be in place. Integration should be executed. However, knowing about dissimilar identities helps organisations create an integration process that respects and manages identity-related challenges and issues like political struggles, delicate client transfer, everyday friction and employee retention. From our experience, an interesting approach is to execute a rather reversed assimilation in those cases by identifying the strongest identity-related assets of the acquired company as it seems beneficial to let the acquired company influence the identity of the acquirer. In any case, when proceeding with integration despite dissimilar identities to follow business strategy, the expectations of this acquisition need to be managed. Minor loss of talent and clients need to be calculated from the beginning as accompanying costs.

3 – Acquirers without a brand architecture strategy in place

Many B2B companies, however, do not have a clear brand architecture strategy in place. Only using organisational identities as the deciding factor would lead to different strategies with every acquisition, leading to confusion, irritation, friction and unsatisfaction among internal and external stakeholders and is not recommended.

4 – Identity in mergers

In a merger, companies with similar identities will get a more rewarding case to combine their companies and a better likelihood to come out successfully. Merging dissimilar identities, on the other hand, presents an almost unsolvable challenge. In these cases, we recommend creating a completely new company with an entirely new identity.

Migrating two companies into one does not only have a strategic component, but also a visual one. At IDna Group we know that design is the most powerful marker of change. And by changing logos and names of the merging companies, management signals valuation and acknowledgement of both companies towards internal and external stakeholders. Knowles et al. studied 216 companies formed by larger mergers in regards to their stock performance (from the date of the deal’s closing to three years after the merger was complete) and their chosen merging strategy expressed by visual cues. The result: companies using an assimilation branding strategy (name and logo of one company dissolve completely into the other) fell short of the market return by 15% on average, and companies using a business-as-usual or federation strategy (continuing two separate entities with names and logos) fell short by 25%, but companies using a fusion strategy exceeded the market return by 3%. In the fusing strategy branding elements like name and logo from both companies were combined into a new name/logo (source).

Contact

Related insights

Identity first: The key to lasting strategic impact

Many of us have heard the numbers… 60-70% of all strategies fail. And if we go all the way back…

Aligning the organisation for transformation and growth

After a busy time with exciting projects, we had the opportunity to reflect on one of our customers’ pervasive challenges.…

Crafting company names with an Identity-driven approach

In the dynamic realm of business, a company name is more than a mere identifier – it’s a powerful vessel…

In the pursuit of talent – how identity can help shape and strengthen your employer brand

Research shows that most leaders are facing severe challenges onboarding the right competencies to the company. In addition, many encounter…